Demystifying Dependency Injection - What It Is and Why It Matters

M ost projects use Dependency Injection in some form. However, many developers take it for granted and do not really question what it is or why they are using it in the first place. This article aims to answer those questions, even though they are rarely asked.

This article is part of a series that goes in depth on Dependency Injection (DI). In this series, we learn what DI actually is and why we would want to use it. Once you start digging into it, you will encounter quite a few related terms, which will be explained. There are also multiple ways to inject dependencies, with even more names and smaller variations. We will cover those and also explore the different ways dependencies can be wired and which frameworks can help us do that.

Problem

Let’s first get everyone on the same page by explaining the basic concepts: What is a dependency?

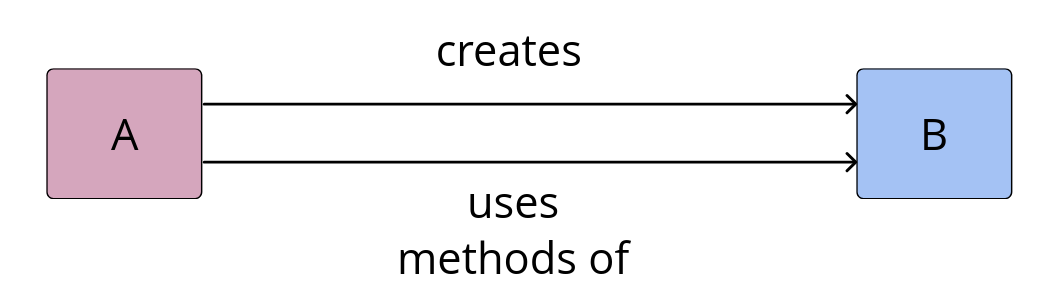

We can explain this easily using the image above. What we see is a class A that uses methods of a class named B. This means B is a dependency of A.

Simple as that. But we are also introducing a problem here, because in this case A creates an instance of B.

If we were to express this as code, it might look like this:

class UserService {

UserRepository userRepo = new UserRepository(...);

List<User> getActiveUsers() {

return userRepo.findAll().stream()

.filter(User::isActive)

.toList();

}

}

Here we see some Java code. The naming looks a bit like Spring, so you might already have a rough idea of the responsibilities of the classes.

The UserService (formerly class A) creates a UserRepository (formerly class B). The repository might access a database or something similar.

This turns out to be problematic, because it violates the Single Responsibility Principle. The UserRepository is not just a dependency, the UserService also creates it.

By creating it, the service becomes responsible for its lifecycle. And if the repository opens a connection to a database or something similar, the service is also responsible for ensuring that the connection gets closed at some point. If you think this is an odd responsibility for a service that should handle users, you are absolutely right.

But this is not the only issue. We also introduce tight coupling between these two classes.

It is not possible to test the getActiveUsers method independently of the UserRepository, even though the contract of the repository’s findAll method is clear. It returns a list, but I am not able to test getActiveUsers without it.

Due to this coupling, a change in UserRepository might also cause tests for UserService to fail. For example, a change in the ordering of the returned list, even if ordering is not relevant to the test. In general, we do not want tests to fail when details we are not testing for, change.

Solution

We introduced several problems by wiring our dependencies this way, but there is a solution that addresses all of them. And as you might have guessed from the title, that solution is Dependency Injection.

Instead of creating the dependency where it is needed, we inject it from the outside. Below is an example of injecting a dependency through the constructor:

class UserService {

UserRepository userRepo;

UserSerivce (UserRepository userRepo) {

this.userRepo = userRepo;

}

List<User> getActiveUsers() {

return userRepo.findAll().stream()

.filter(User::isActive)

.toList();

}

}

The lifecycle of the UserRepository now lies outside of the UserService. Where it is created and who manages it will be discussed in another article in this series (about wiring).

This approach also solves the problem of tight coupling. Independent testing is now possible. It is easy to create a simple mock of UserRepository that returns a static list of users and pass it into the service. We can simply use the constructor to inject the mock instead of the actual implementation.

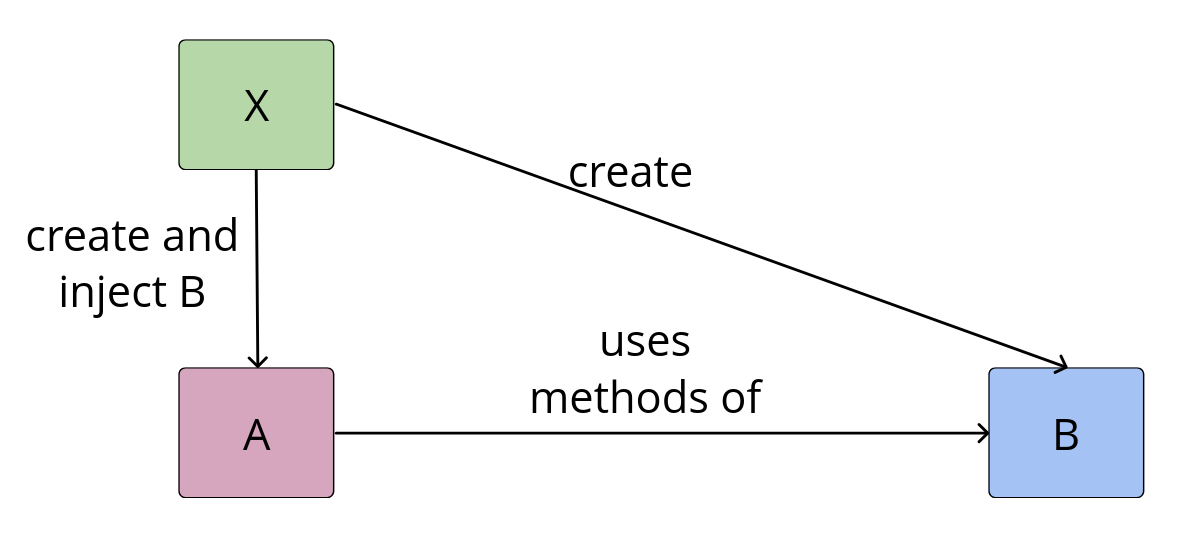

Because we changed the code, the diagram changes as well.

Class A still uses methods of class B, but this is now the only arrow in that direction. There is another component, X, that handles the creation and injection of dependencies. To use proper terminology going forward:

X is the injector, A is the client, and B is the dependency.

Conclusion

As we have seen, Dependency Injection enforces separation of concerns. The creation and usage of a dependency are now separated by injecting dependencies from the outside.

This enables us to test units in isolation.

There are multiple ways to inject dependencies, which will be covered in another part of this series.

DI can also be implemented in different ways, either manually or with a framework. Frameworks may inject dependencies at compile time or at runtime. These topics will also be explored in future articles.